Usability and availability are somewhat different lenses to assess user experience. It's possible to become strong in one area and weak in the other. Using either strategy alone could bring about an inaccurate opinion of your website's user experience. Evaluating your website with both accessibility and usability in mind gives all users the greatest possible user experience.

Usability relates to how simple things are to utilize. Typically, usability is measured against five criteria--memorability, efficacy, errors, learnability, and satisfaction (MEELS).

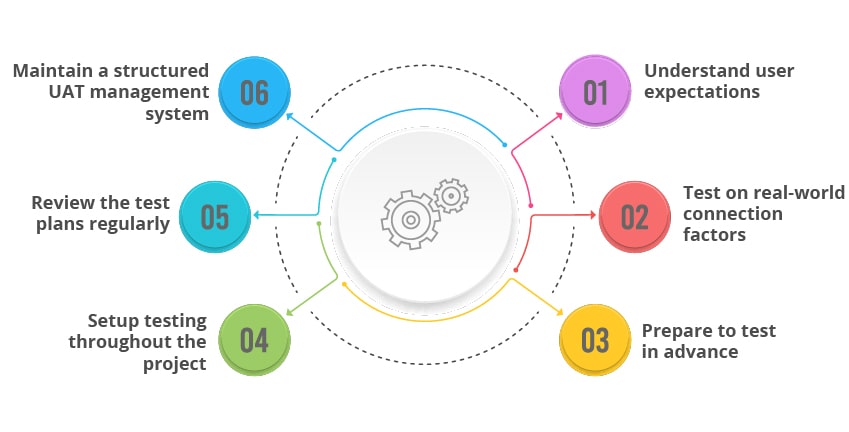

In support of these criteria, inquire about the following when evaluating UAT:

- What tasks are users expected to complete using the website?

- How easily can someone finish those jobs?

- What test scenarios could evaluate the end of those jobs?

- What data if you record to capture in analyzing those tasks?

- How suited is your user using the actions necessary to complete the tasks?

- Whenever you have answered those questions, ask what and how things should change to enhance user experience. Normally, traditional usability testing doesn't look at the disabled user. We feel that maintaining all users in your mind is very important to your website's success, though.

Access relates to the way the handicapped person uses something. Department 508 demands that all government sites are accessible to disabled users. Section 504 expands these access requirements to any group receiving federal funding.

Available sites present information through various sensory channels, for example, sight and sound. This multisensory approach enables disabled users to get the same information as nondisabled users. As an instance, if you've got a movie on your website, you must provide visual access into this audio data through in-sync captioning.

However, keep in mind that supplying a secondary channel to satisfy the Section 508 requirements does not ensure that handicapped users will have an equal and positive encounter on your site. You have to design your secondary station with both audience and context in mind.

By way of example, if an image is decorative, you need to label it with null alt text, which tells the screen reader to skip over it. But when an image communicates advice, like a chart, you need to think about:

- What info does the alt text convey?

- What exactly does the surrounding text say about the graph?

- What's your take-home message of this chart?

- Poor focus on audience and context lessens the disabled individual's user experience. Thus, analyzing these secondary stations becomes as important as testing the principal channels.

Tying Things Together: Usability and Access Best Practices

Although many usability books and articles offer the perfect number of users to examine, they seldom deal with the value of diversity in evaluation subjects. When selecting test pools, testers often concentrate on"the average user" This, nevertheless, is at the expense of smaller consumer groups--for example handicapped individuals.

Leaving disabled folks out of usability testing makes a difference in testing methodology. For example, a new navigation menu on a site may test nicely with nondisabled consumers and get great scores in all of the MEELS categories. However, if the color contrast isn't sufficient, or so the menu isn't labeled to use screen readers, or even the keyboard-based navigation properly, blind and also low-vision consumers won't be able to use it.

By not examining with handicapped individuals, it is possible to have a whole website with higher satisfaction and robust usability to get a nondisabled population. Although this population may indeed be the desired"average site consumer," your site may be wholly unusable--and inaccessible--to the disabled population.

So next time you evaluate your website, maintain all your users in mind, and make sure that it is an equally successful experience for everybody.

Comments

Post a Comment